Key facts:

- Lassa fever is endemic to parts of West Africa and is responsible for an estimated 300,000 – 500,000 infections, causing 5,000 deaths annually.

- This outbreak constitutes the largest recorded epidemic of Lassa fever in Nigeria to date.

- Transmission can occur through direct contact with the blood or secretions of an infected person, or following contact with objects contaminated with urine or faeces of infected rodents. Lassa fever incubation period ranges from 6 to 21 days.

- Efficacy of ribavirin has been demonstrated if administered during the first 6 days of illness and is indicated for post-exposure prophylaxis and treatment of Lassa fever.

- Intravenous ribavirin was made available for treatment of confirmed cases in 3 of the most affected states (Edo, Ondo and Ebonyi).

What is the situation on the ground?

The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) has been leading a multi-partner response to the Lassa fever outbreak in collaboration with the State Ministries of Health, local government health departments, the national Lassa fever Emergency Operations Centre (EOC), the WHO, ALIMA and Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

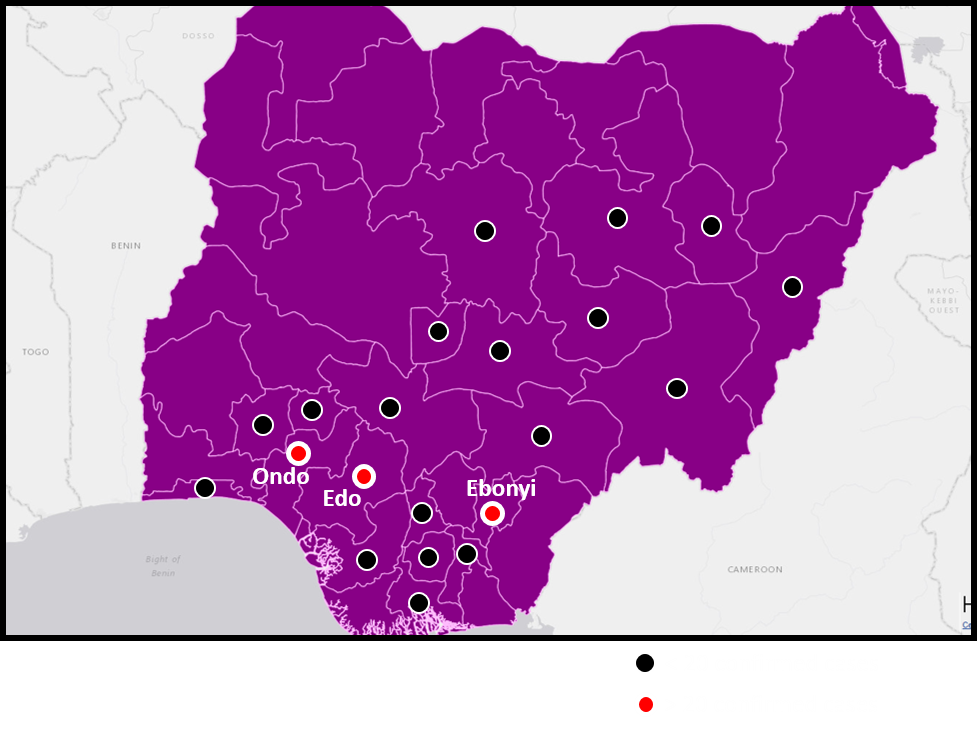

From the 1st of January to the 27th May 2018, a total of 441 confirmed cases have been reported, resulting in 108 deaths and a fatality rate of 25.1%. A large geographical area was affected as cases were detected across 21 states of Nigeria, with the regions most affected being the Edo (42%), Ondo (24%) and Ebonyi (15%) states. The number of reported cases begun a downward trend from mid-February 2018 onwards.

Distribution of confirmed cases of Lassa fever virus according to states of Nigeria (purple). Figure based on the NCDC situation report as of 27th May 2018.

Phylogenetic analysis of 27 Lassa viruses detected during the outbreak was performed on site by researchers at the Irrua Specialist Teaching Hospital (Edo State) in collaboration with partners from the Bernhard-Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (Germany) and others. Real-time sequencing revealed key facts important for control efforts.

The viruses sequenced appeared epidemiologically distinct, showing the independent introduction of different viruses that are consistent with the pool of lineages circulating in Nigeria during previous outbreaks. This excluded the possibility of an emerging new virulent strain of Lassa virus and indicated the most likely route of transmission being spill over of virus from the rodent reservoir, rather than extensive human-to-human transmission. Concerning the prevention of future Lassa fever outbreaks, these findings highlight the importance of community engagement and promoting hygienic conditions to discourage rodents from entering homes.